From Arup to SimpsonHaugh and Partners, architects are reaping the efficiencies of automated design. AIA partner Bentley Systems explores what’s happening and what’s to come.

As most designers know, architecture is a blend of art and science.

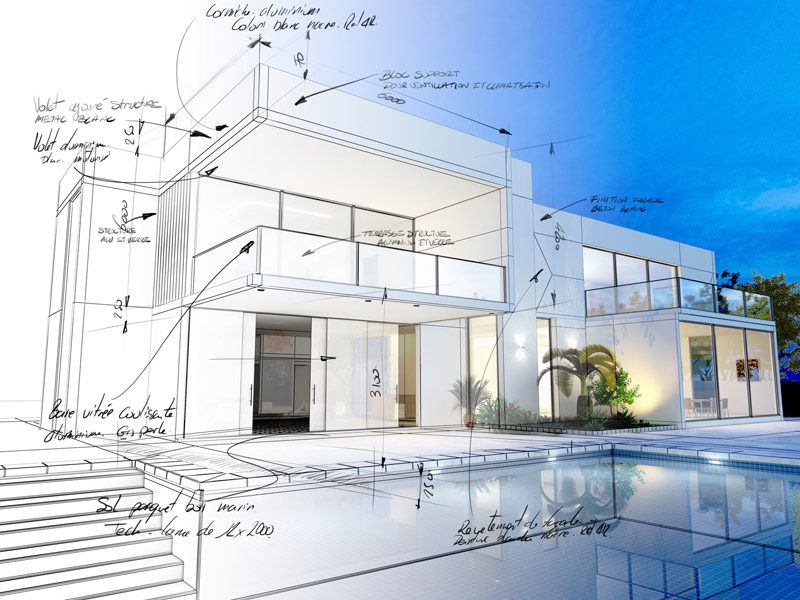

The architectural design process requires the designer to synthesize a lot of varied information and evaluate all possible ideas. Automated design helps evaluate these possibilities because the computer can look at more alternatives in less time. This ability allows architects to quickly seek an optimal end state of quality or value. It also helps mitigate risk because designers can see all the potential problems prior to real-world construction, saving time and money.

Architects around the world have been successfully implementing automated design for several years. For the iconic One Blackfriars building in London, SimpsonHaugh and Partners created a parametric design model to virtually explore solutions and options. Using applications that allow for automated design techniques helped SimpsonHaugh designers quickly calculate and produce visuals in just two days instead of over multiple weeks. The result was an outstanding tower design created with fewer people and errors in less time.

In 2013, Arup was tasked with designing the Las Vegas High Roller Observation Wheel. The team created a parametric model for automating the design process and accelerating the design iteration using Bentley applications. The parametric model set all the variables for the wheel geometry and discovered which dimensions drove the design, saving the client time and money.

Nothing to fear

While the benefits of automated design are significant, many architects have concerns. The most common is that computers will eventually replace architects, that computers will be able to recognize what people find aesthetically pleasing using machine learning, if fed the right parameters. However, while computers are very good at defined tasks—solving engineering calculations and making simple judgments on quality—these tasks are all based on patterns and not feelings or emotions.

When a human architect sits down and starts thinking about designing a building, they consider the five human senses. They think about how the light will stream through a grand window in the atrium or how the materials will stroke emotion in the people as they walk through. Computers cannot work at this sensory and emotional level, cannot understand a building’s poetry of emotion, like human architects can.

Another reason humans will not be going anywhere anytime soon is because computers can’t adequately replace the communication between architect and client. As most architects discuss design intent with their client and explain why they made certain decisions, they evaluate the client’s emotional and practical responses. If there appears to be hesitance or disapproval, the designer can sense this and begin discussing alternatives; if there appears to be excitement and approval, the conversation can continue.

What’s next?

Right now, automated design focuses on the idea of BIM methodology, which simulates facilities and buildings. However, as these types of simulations advance, people will want more. To accommodate this demand, one way that automated design will advance is simulating businesses, with BIM processes as an input. Architects will evaluate if the space can adequately fit within what users want, and they’ll know a lot sooner whether they can deliver the building within budget while creating an immersive design and visualizing everything. This practice will also allow for more project components to be constructed off-site in a controlled environment to meet all the requirements, shipped to the site, and plugged into the building. By including automated design in the architectural workflow, designers can reap significant benefits and create designs that they never thought possible.

Source: American Institute of Architects