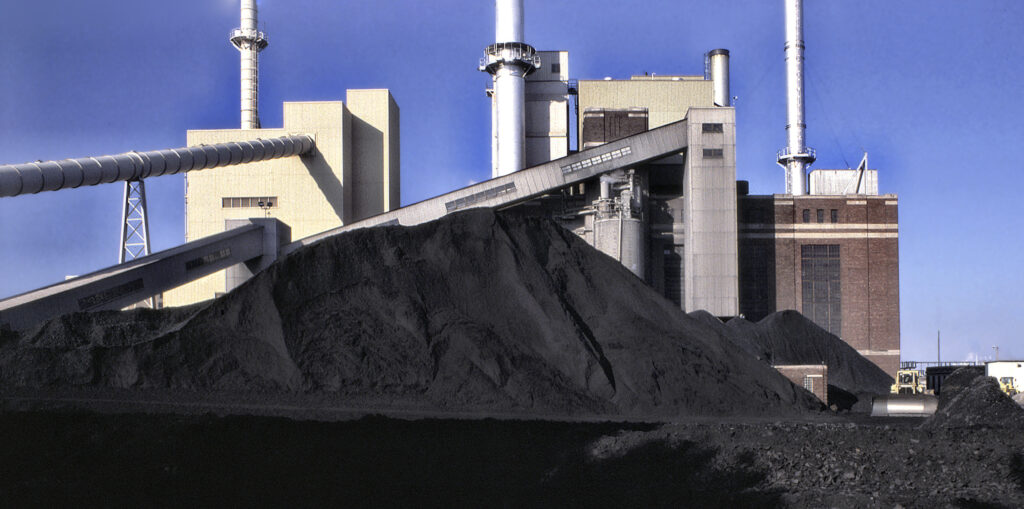

In 2020, the city greenlit a strategy to close the Fayette Power Project plant, intending to eradicate carbon emissions. However, various political, economic, and technological challenges have arisen since then.

Two Pivotal Dates Define the Struggles of Fayette Power Project’s Future:

In recent years, two significant dates have come to define the uncertain path of the Fayette Power Project, a coal-fired plant situated near La Grange.

The first date, March 26, 2020, marked a crucial decision by the Austin City Council. They approved an ambitious emissions-reduction plan, outlining the shutdown of their share of the plant by the end of 2022, all in the name of eliminating carbon emissions.

The second date, August 17, 2023, holds its own significance. Austin Energy, after falling short of the 2022 target, managed to generate a staggering $11 million in a single day from the plant.

Austin has been at the forefront of a rapid shift away from fossil fuels, outpacing the rest of the state. Today, the Fayette plant is primarily responsible for Austin Energy’s remaining carbon emissions. However, closing the plant to combat climate change has proven far more challenging than envisioned. Its continued operation highlights the legal, economic, and technological hurdles faced by cities in their mission to reduce emissions, compounded by market incentives that run counter to the goal. Notably, rising power demand in Texas and alterations to the state’s electricity market have enhanced the financial allure of coal power, despite its status as the dirtiest energy source concerning carbon emissions.

In a public meeting held in August, Austin Energy General Manager Bob Kahn emphasized the need for a “course correction” to reevaluate the utility’s resource generation plan, which, for now, still includes power sourced from the Fayette coal plant. Nevertheless, the city remains steadfast in its ambitious objective of achieving 100% emissions-free electricity by 2035.

Austin isn’t the only Texas city pursuing such goals. Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio share aspirations of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, aligned with the targets set in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. However, cities and private utilities also contend with the imperative of keeping costs manageable for customers, complicating efforts to part ways with plants like the Fayette Power Project.

Texas currently hosts 13 operational coal plants. Data from the Energy Information Agency reveals that since 2012, seven plants have been fully decommissioned, while another four intend to retire some or all of their units before 2030.

Austin Energy operates on two levels of the state’s electricity market. It contracts with wind and solar farms, owns natural gas, coal, and nuclear power generation, and sells their power wholesale onto the grid. The Electric Reliability Council of Texas manages the grid to maintain the balance of supply and demand. Electric providers, including Austin Energy, buy the power through the market managed by ERCOT and distribute it to Texans.

In the aftermath of the 2021 winter storm, during which demand for power was on track to outpace supply and forced widespread power outages across Texas, ERCOT revamped its market model, changing the economic incentives to encourage the development of energy sources that can quickly add more power to the grid at a moment’s notice. Energy experts call this ‘dispatchability.’

This year, ERCOT is creating financial incentives to encourage power generators to expand their ancillary services, a system in which power generators hold a portion of their total power generating capacity on the side, ready to provide more to the grid when demand threatens to outpace supply. Over the summer, ancillary services have also been used on especially hot days when the sun is setting, and solar power production slows down, says Michael Enger, the director of energy and market operations for Austin Energy.

“Every time you have a new ancillary services product that has to do with dispatchability, power plants that are dispatchable like coal and natural gas benefit from it,” Enger said.